Capybaras stack for several key reasons: warmth (especially in cooler weather), social bonding to strengthen group ties and reduce stress, and safety from predators by appearing larger and having more eyes and ears alert. It’s a cooperative behavior that shows trust and comfort, not dominance or stress.

What is Capybara Stacking? A Behavioural Deep Dive

Defining the Phenomenon: What Stacking Looks Like

Capybara stacking is exactly what it sounds like, one or more capybaras resting directly on top of another, forming a living “pile.” Sometimes it’s just a pair: one reclining comfortably across a companion’s back. Other times, it can be a small heap of three or more, layered like logs in a bundle. Unlike aggressive dominance displays seen in other animals, stacking in capybaras is calm, gentle, and almost always mutual.

Common Scenarios

This behaviour most often occurs during rest or sleep, when the group is relaxed. You’ll spot stacks on grassy riverbanks, in shaded resting spots, or even partially submerged in water (where capybaras spend much of their time). Stacking serves as a form of communal downtime, reflecting both trust and social bonding.

Participants

Stacking isn’t limited to a particular age or gender. Juveniles frequently climb onto adults for warmth and security, much like human children snuggling close to a parent. Adults, too, engage in stacking with one another, especially in larger herds where physical closeness is a natural part of daily life. In mixed groups, you might see younger capybaras lounging on older ones, or multiple siblings piling together in one fuzzy cluster.

Capybara Social Structures: The Foundation of Group Behaviour

Herd Mentality

To understand stacking, it helps to recognize how social capybaras truly are. Unlike solitary rodents, capybaras thrive in groups. In the wild, herds typically range from 10 to 20 individuals, though in resource-rich areas, groups can swell to 40 or more. Living together provides safety: with many eyes watching, predators like jaguars or caimans are less likely to succeed.

Group Dynamics

Within these herds, roles emerge. A dominant male usually leads, maintaining access to mates and defending the group’s territory. Females often form the majority and share responsibilities like grooming and guarding young. Subordinate males and juveniles round out the social web. While hierarchy exists, capybara society leans heavily toward cooperation and tolerance rather than conflict, qualities that make stacking both possible and practical

Field studies of wild capybaras in South America, particularly in the wetlands of Venezuela and Brazil, have documented these social tendencies consistently. Observations confirm that resting in close contact, including stacking, reduces stress, strengthens group bonds, and reinforces the communal fabric that defines capybara life. In short, stacking isn’t a quirk; it’s a natural extension of their deeply social instincts.

The Core Reasons Capybaras Stack: Scientific Explanations

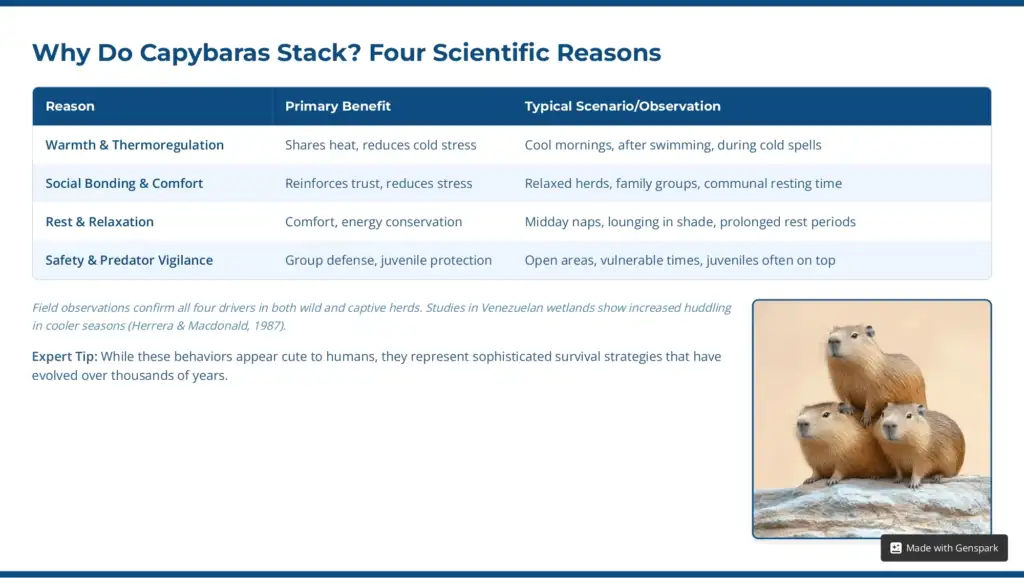

Capybara stacking isn’t random; it reflects practical survival strategies and deep social instincts. Researchers and field observers point to four primary drivers: warmth, bonding, rest, and safety.

| Reason for Stacking | Primary Benefit | Typical Scenario | Scientific Evidence/Observation |

| Warmth & Thermoregulation | Strengthens relationships, reduces stress, and provides security | Cooler evenings, after swimming, during cold spells | Field studies in Venezuelan wetlands not huddling increases in cooler seasons (Herrera & Macdonald, 1987) |

| Social Bonding & Comfort | Strengthens relationships, reduces stress, provides security | Resting periods, family groups, relaxed herds | Napping, prolonged inactivity, and shaded resting spots |

| Rest & Relaxation | Physical comfort, efficient rest, energy conservation | Zoo studies show capybaras prefer body contact during rest, even when the temperature is mild | Zoo studies show capybaras prefer body contact during rest, even when temperature is mild |

| Safety & Predator Vigilance | Collective defence, early predator detection, juvenile protection | Sleeping in open areas, vulnerable times | Observations in the Pant anal report juveniles often resting atop adults for protection |

1. Warmth and Thermoregulation

Capybaras spend much of their lives in and around water, which can quickly drain body heat. By stacking, they reduce exposed surface area, sharing warmth much like penguins in cold climates. Huddling is particularly noticeable during chilly mornings, cool evenings, or after long swims.

Capybaras also lack thick insulating fur, another reason close body contact is an effective survival tactic. Their physiology is adapted for warm, humid environments, so when temperatures drop, communal body heat becomes essential.

Expert Tip: If you see capybaras stacking tightly together, temperature is usually the driver. Looser, more casual stacks are often about comfort or bonding rather than warmth.

2. Social Bonding and Comfort

Beyond temperature, stacking is a powerful form of social glue. Physical closeness helps reinforce herd cohesion and trust, ensuring members feel safe within the group. Capybaras are tactile creatures; they groom each other, vocalize softly, and frequently maintain skin-to-skin contact.

Stacking extends these behaviours by providing both psychological comfort and emotional reassurance. Resting against the warmth of a herd mate reduces anxiety and promotes calm, similar to how humans feel soothed by a hug.

Expert Tip: Look for additional body-language cues: relaxed postures, half-closed eyes, or gentle grooming. These signs confirm stacking is about comfort, not stress.

Differentiation Opportunity: Animal behaviour studies across mammals, including primates, show that physical touch reduces cortisol (stress hormone) levels. Capybaras may gain similar benefits from their close contact.

3. Rest and Relaxation:

Sometimes, stacking is simply about comfort. A capybara makes an excellent pillow, after all. Resting against a herd mate provides stability, softness, and a secure spot to nap.

Efficient rest is critical for capybaras, which are crepuscular, most active at dawn and dusk. Stacking during the day conserves energy, helping them remain alert and responsive during feeding and predator-vigilance periods.

Expert Tip: Notice the difference between tight cold-weather huddles versus loose, comfortable lounging stacks. The latter is more about social bonding and relaxation than heat.

4. Safety and Predator Vigilance

Stacking also has survival advantages. A cluster of capybaras appears larger and more intimidating, potentially deterring predators such as jaguars, caimans, or large birds of prey. More importantly, close contact means more eyes and ears remain alert, increasing the herd’s chance of detecting danger early.

Juveniles often climb atop adults during these periods, gaining both protection and a higher vantage point. Adults, in turn, seem to tolerate this behaviour, suggesting an instinctive protective role.

Expert Tip: A stacked herd at rest in an open field is not only bonding but also broadcasting strength in numbers, turning vulnerability into collective defence.

Field observations in the Brazilian Pantanal confirm that predator pressure strongly influences herd behaviour. Researchers have noted increased clustering and huddling in areas with high predator density.

By combining these four drivers, warmth, bonding, rest, and safety, capybara stacking emerges as a multipurpose behaviour: adorable to us, but vital to them.

Beyond the Basics: Deeper Insights into Stacking Behaviour

Common Misconceptions

Capybara stacking may look unusual, but much of what people assume about it is inaccurate. Let’s clear up some of the most common myths:

- “They stack to show dominance.”

While capybaras do have social hierarchies, stacking is not about dominance. Unlike primates or wolves, who use mounting or positioning as power displays, capybaras stack calmly and voluntarily. Ethologists note that the behaviour is cooperative, reflecting comfort and trust, not competition. - “They do it because they’re bored.”

Far from being a product of boredom, stacking has clear practical functions: warmth, security, bonding, and rest. Even in stimulating natural environments, wild capybaras exhibit the same behaviour, proving it’s instinctive, not a filler activity. - “Stacking is a stress response.”

On the contrary, stacking signals relaxation. Stressed or threatened capybaras scatter, dive into water, or produce sharp alarm calls. Stacking occurs when they feel safe, calm, and secure. It’s one of the clearest visual indicators that a herd is at ease.

The Scientific Truth

Stacking aligns with what ethologists describe as allo-positive behaviour, interactions within a species that strengthen cooperation and cohesion. Field studies in the Brazilian Pantanal confirm that behaviours like stacking and communal grooming reduce stress, increase group harmony, and enhance reproductive success (Herrera & Macdonald, 1987).

Nuanced Understanding: Expert Insight

“Capybara stacking is a fascinating display of their advanced social intelligence,” explains Dr. Julia Mata, a zoologist specializing in South American mammals. “It reinforces herd cohesion while serving practical survival functions, something we rarely see expressed so clearly in other large rodents.”

Q&A with experts often highlights that:

- Triggers: Cool weather, post-swimming rest, or juvenile play often initiate stacking.

- Significance: Stacking reflects high tolerance levels and low aggression, hallmarks of capybara society.

- Intelligence: The choice of who stacks on whom often correlates with social bonds, offspring with mothers, siblings together, or trusted companions side by side.

Survival Advantage

Stacking isn’t just cute; it may offer evolutionary benefits. That increase warmth, reduce stress, and strengthen group cohesion improve overall survival odds. In highly social species like capybaras, these bonds can directly influence reproductive success, as stable herds are more likely to raise offspring safely.

Non-Verbal Signals in Stacking

Stacking can also be read as non-verbal communication:

- Who stacks on whom often reflects trust. Juveniles seek security from adults, while peers lounge comfortably together.

- How tightly they cluster can signal environmental needs: tight piles for warmth, loose lounging for comfort.

- Relaxed stacks (eyes half-closed, soft chirps or purr-like calls) communicate trust and well-being across the herd.

Climate and Environmental Variations

Researchers suggest that stacking may vary depending on the environment:

- Cooler Climates: More frequent and tighter huddles, especially at night.

- Tropical Wetlands: Looser stacks during daytime rest, as warmth is less of a factor.

- Captive vs. Wild: In well-managed zoos and sanctuaries, capybaras often stack more visibly because space brings groups closer together, but the motivation remains the same: comfort and cohesion.

Expert Tip: If you observe captive capybaras stacking often, it’s not a sign of stress; it’s a sign that they feel secure enough to relax in close company.

By peeling back the myths and looking at the deeper drivers, evolutionary advantage, social communication, and environmental influence, we see stacking for what it truly is: not a quirk, but a finely tuned behavior that has helped capybaras thrive for millennia.

Addressing Common Concerns: Is Capybara Stacking Normal?

Dispelling Distress Myths

One of the most frequent questions from first-time observers is: “Are the capybaras uncomfortable? Are they being squashed?” The good news is that stacking is completely normal and, in fact, a sign of well-being. Unlike stress behaviors, which include scattering, alarm calls, or sudden dives into water, stacking happens only when capybaras feel safe and at ease.

Signs of Well-Being

When stacking is observed in relaxed contexts, such as during midday naps or gentle grooming sessions, it indicates that the herd is content. Look for additional clues: half-closed eyes, soft vocalizations (often described as purrs or chirps), and still, loose postures. These are clear markers that the group is comfortable, not distressed.

Audience Pain Point: If you’ve ever worried that stacking might mean a capybara is under pressure or being dominated, rest assured, scientific observations consistently show the opposite. Stacking is a form of closeness and bonding, not conflict or discomfort.

Integral to Survival

Stacking isn’t just “cute behaviour.” It’s part of a broader set of group strategies that help capybaras survive. Herd living provides warmth, safety, and emotional stability, and stacking strengthens these benefits. By maintaining strong social bonds, herds are more resilient in the face of predators and environmental challenges.

Social Hierarchy vs. Cooperation

Capybara herds indeed operate with a social hierarchy, typically with one dominant male, a majority of females, and subordinate males. However, stacking is not about enforcing that hierarchy. Instead, it highlights the cooperative side of capybara society: individuals resting together, juveniles climbing on adults for comfort, and herd members reinforcing mutual trust.

Expert Tip: While hierarchies exist, stacking is much more about comfort, warmth, and social bonding than dominance. Think of it less as “pecking order” and more as “community snuggling.”

In short, stacking is a healthy, adaptive behaviour that signals security and contentment within a herd. If you see capybaras stacked together, you’re witnessing one of the purest expressions of their gentle, cooperative nature.

Conclusion: Embracing the Endearing Logic of Capybara Stacking

Capybara stacking may look like a whimsical quirk, but science shows it serves important purposes. By piling together, capybaras conserve warmth, strengthen social bonds, find comfort and rest, and enhance safety against potential threats. These benefits are deeply interconnected; what begins as a way to stay warm also fosters trust, relaxation, and herd cohesion.

When we look past the viral images and memes, stacking reveals itself as more than just adorable; it’s a window into the complex social intelligence of the world’s largest rodent. Every pile of capybaras tells a story of cooperation, survival, and community.

As observers, we’re invited to see these animals with fresh eyes: not just as internet celebrities, but as living examples of how connection and cooperation shape life in the wild.

Call to Action: The next time you come across a photo or see capybaras in person, pause to appreciate the deeper logic behind their behavior. And if this sparks curiosity, turn to reputable zoological studies and wildlife experts, because the more we understand, the better we can respect and protect the remarkable creatures we share the planet with.