Introduction

Capybaras have a reputation that’s hard to beat.

They’re calm. They’re social. And they’re constantly starring in those viral “world’s chillest animal” videos, lounging in hot springs, letting ducks nap on their backs, or just hanging out like the zen masters of the rodent world.

So naturally, you start to wonder…

Do they ever bite?

I did too. As someone who genuinely loves these gentle giants, I went digging for the real answers. And what I found was surprisingly helpful, and yes, a little bit alarming.

In this guide, I’ll break it all down for you:

- Can capybaras bite humans?

- How strong is their bite, really?

- Why would they bite in the first place?

- What do you do if one bites you?

- Could it carry diseases like rabies?

- And most importantly, how can you stay safe around them?

Let’s dive into the facts so you can keep your curiosity (and fingers) intact.

Table of Contents

Do Capybaras Bite Humans? (Quick Answer)

Here’s the straight truth:

Yes, capybaras can bite.

But no, they’re not out looking to.

These 100+ pound rodents are famously docile and social. They’re the kind of animals that would rather squeak, waddle away, or sit politely in a corner than start trouble.

But, and this is important, they’re still wild animals.

They have large, sharp front teeth.

And under the wrong circumstances? Those teeth can do damage.

Capybaras usually bite as a reflex or defensive reaction.

Here’s when that might happen:

- They feel threatened or cornered

- They’re startled suddenly.

- They mistake your hand for food (especially if it smells like veggies)

- They’re stressed or in pain.

If none of those things are happening? You’re probably fine.

In normal, calm situations, they’re more likely to walk away than lash out.

But don’t get too comfortable, just because bites are rare doesn’t mean they’re harmless.

These animals have serious bite force (we’ll talk numbers in the next section), and if a bite happens, it can pierce skin, cause bleeding, and even get infected if not treated properly.

To sum it up:

Capybaras are chill by nature, but like any animal with teeth, they can bite if provoked, scared, or pushed past their limits.

In the next section, we’ll look at how strong a capybara bite really is, and why you shouldn’t underestimate those big rodent chompers.

How Dangerous Are Capybara Bites? (Real Incidents and Injuries)

Capybaras may look cuddly, but don’t let the soft fur fool you; those front teeth are no joke.

Like all rodents, capybaras have ever-growing incisors: two on the top, two on the bottom. And they’re not just for chewing plants. These teeth are chisel-sharp, and when they clamp down, they can act like wire-cutters, slicing straight through skin and muscle.

One person once described a capybara bite as “like having a pointed steel wedge shoved into your flesh.” That’s not an exaggeration. The shape of their teeth means even a single bite can lead to deep puncture wounds, long lacerations, and crushing damage.

And the risk doesn’t end there, because when those wounds go untreated, infections, abscesses, and nerve trauma can follow.

Let’s take a look at a few real bite cases to understand just how serious capybara bites can be.

Case 1: Woman Bitten While Rescuing Her Dog

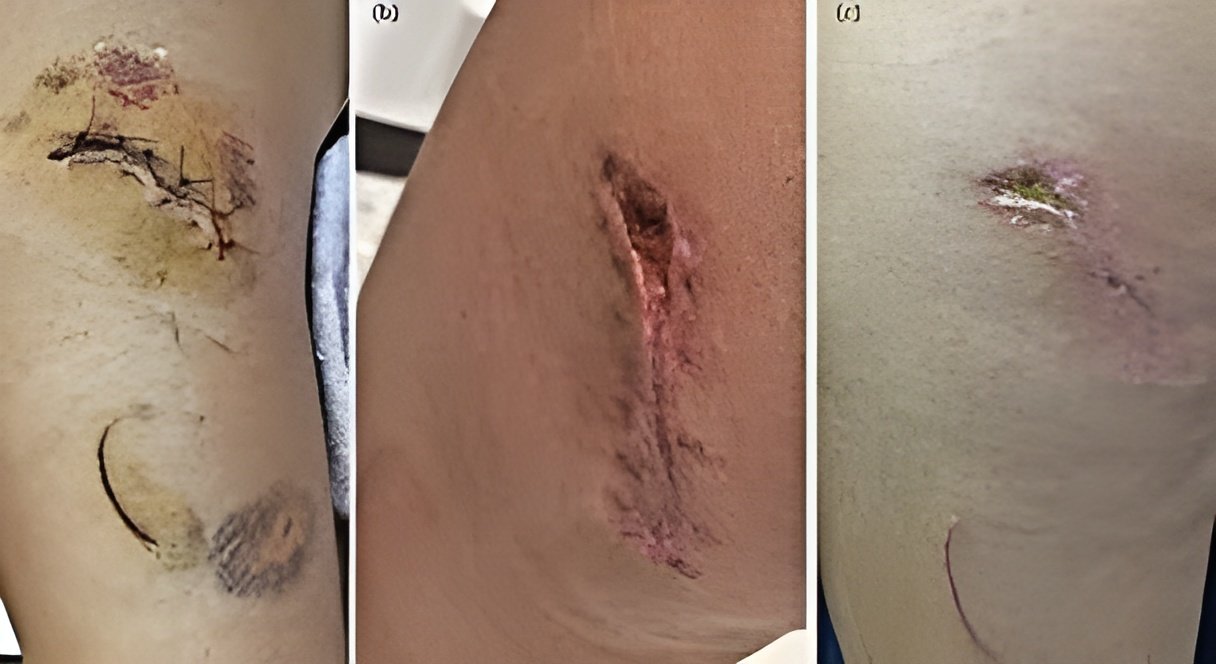

In Brazil, a 25-year-old woman tried to save her dog from a wild capybara that had suddenly gone on the attack.

The capybara turned on her, biting deep into her left thigh and scratching her legs in the process. She needed emergency stitches, antibiotics, rabies shots, and tetanus treatment.

Even after all that, the wound developed a painful abscess that required surgery. Once healed, she was left with 8 cm scars across her thigh.

The most heartbreaking part?

Her dog didn’t survive. The bite injuries were too severe, and it passed away two days later.

This case is a harsh reminder: if you step between a capybara and what it perceives as a threat, even your pet, you’re risking serious injury.

Case 2: Man Bitten on the Thigh, Hospitalized

Another bite case out of Brazil involved a 54-year-old man who ended up in the ER after being bitten on the thigh.

He arrived with blood soaking through a compression bandage, and doctors found two deep gashes and multiple scrapes. He was immediately put on antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate) and given rabies prophylaxis just in case.

Science Direct has covered this case completely.

Thanks to prompt treatment, he healed without complications, but this case proves how critical it is to get medical attention fast. Even a single bite requires full wound care and infection prevention.

Case 3: Children Bitten at a Petting Zoo

Capybaras are often featured at petting zoos because of their gentle image. But even in calm, captive settings, bites can happen.

At a safari park in eastern Japan, a capybara bit two children during a visitor encounter.

One girl had a gash from her ear to the back of her head that required nine stitches and took two weeks to heal. The other child’s injuries were minor by comparison, but still required care.

Zoo staff quickly transported the injured child to a hospital and issued a public apology.

Here’s the scary part: a child’s height makes their head and neck easier targets, and in this case, if the bite had hit a major artery, the outcome could’ve been much worse.

Case 4: Pet Capybara Accidentally Bites Owner’s Thumb

Not all bite cases are wild attacks; some happen during affectionate moments.

One capybara owner shared a story about feeding their pet capybara cheese-flavored snacks and letting it lick Cheetos dust off their fingers.

That was the mistake.

The capybara mistook the person’s thumb for food and chomped down hard. The bite caused a pool of blood, sent nearby children screaming, and left the owner with a deeply cut thumb.

The lesson?

Never feed a capybara by hand.

Even a friendly one can confuse fingers for snacks, and their bite isn’t something you’ll walk off.

Case 5: Wild Capybara Attacks Swimmer in Viral Video

This final story made headlines.

In Colombia, a woman was swimming in a lake when a large capybara suddenly charged at her in the water.

The attack was caught on video. You can see her trying to back away, even holding up a hand to keep it calm, but the capybara leaps onto her back and starts biting her head and shoulders repeatedly.

A man onshore ran over with a stick to help, and she escaped the water sobbing, covered in bite marks.

While rare, this case shows that capybaras can act aggressively, especially if they’re territorial, sick, or feel cornered. And when they do, they don’t always hold back.

So… How Dangerous Are Capybara Bites?

Let’s break it down:

✅ Bite injuries range from minor cuts to deep lacerations requiring stitches

✅ Some bites lead to abscesses, infections, or nerve trauma

✅ Children are at higher risk due to their size

✅ Dogs can be killed by capybara bites

✅ Every case required medical treatment; these aren’t injuries you can “wait out”

The good news?

So far, there are no reported human deaths from capybara bites. People have survived, often with scars and stories to tell, but not fatalities.

Still, the risk is very real.

Their incisors can slice, puncture, and crush, especially if they clamp onto fingers, thighs, or soft tissue. One wrong move, and a capybara can easily break skin, sever a nerve, or do lasting damage.

Bottom line?

A capybara bite won’t shred you like a lion, but it can land you in surgery, stitches, or worse if ignored.

Up next, we’ll cover why capybaras bite in the first place and how to recognize the warning signs before it ever gets to that point.

Why Do Capybaras Bite? (Triggers and Warning Signs)

Capybaras are usually chill, lounging in ponds, letting birds perch on them, minding their own business.

But when they bite?

There’s almost always a reason.

From territorial instincts to food confusion, capybaras don’t bite out of nowhere. Their reactions are usually tied to fear, discomfort, or miscommunication.

Let’s break down the most common triggers and how to recognize when a capybara might be about to snap.

Feeling Threatened or Cornered

This is reason #1 why a capybara will bite.

In the wild, capybaras are prey animals. Sure, they’re big, but they’re still on the menu for jaguars, caimans, and anacondas. So when a capybara feels trapped or can’t access its escape route (usually water), it may switch to defense mode.

That’s when the teeth come out.

We saw this in the Brazil case, a woman tried to rescue her dog, but the capybara felt cornered and lashed out with a deep bite to her thigh.

You don’t have to be aggressive to trigger this. Even accidentally blocking its path, grabbing it while it’s walking away, or crowding it with excited kids in a petting zoo can be enough to make a capybara feel trapped.

If a capybara doesn’t feel it can flee, it might fight instead.

Protecting Territory or Offspring

Capybaras may be mellow, but they still defend what’s theirs.

In the wild and in captivity, dominant males often guard their territory. And mothers? They’re just as protective, especially when pups are nearby.

If you approach a group of capybaras too closely, especially around babies, one might charge or bite to warn you off. It’s not personal, it’s instinct.

This might explain what happened in the petting zoo incident, where a capybara bit two kids. If the animal felt they were too close or invading its space, a bite may have been its way of saying “back off.”

Bottom line: if a capybara sees you as a threat to its home, food, or family, it may act before you do.

Sudden Startle or Pain

Capybaras don’t like surprises.

If you sneak up behind one, touch it while it’s dozing, or accidentally step on its foot, don’t be shocked if it snaps. It’s a reflex, not a choice.

Even gentle handling can go wrong if the animal is sore, overstimulated, or simply not in the mood.

Their backs are particularly sensitive. They might tolerate birds standing on them in a pond, but they’re not thrilled about humans doing the same.

So if you jolt, poke, or grab one unexpectedly, it might react the only way it knows how, with its teeth.

Food Confusion or Feeding Aggression

This is a common trigger, and a completely avoidable one.

Capybaras are food-driven. If they’re excited about snacks (especially sweet ones), they might accidentally mistake your fingers for food.

One owner learned this the hard way after letting their capybara lick Cheetos dust off their hands. A moment later? The capybara bit into their thumb, thinking it was part of the snack.

Result: lots of blood, a lot of screaming, and a painful lesson.

To avoid this:

- Don’t feed by hand

- Use an open palm or a food dish.

- Never reach into a capybara’s mouth zone with fingers.

- Don’t interrupt them while they’re eating.

They also have poor forward eyesight, so if you wave something small near their nose… it might get chomped.

Aggression Toward Other Animals (And You Get Involved)

Sometimes capybaras fight each other, especially males, during dominance disputes.

They might also clash with other animals, like small dogs, if they feel threatened or territorial.

And here’s the risk:

If you intervene, you could get bitten.

Even if they’re not targeting you, a capybara in “fight mode” won’t always distinguish between friend and foe. Just like breaking up a dog fight can result in accidental bites, trying to physically separate animals can backfire.

If you ever need to intervene, use tools like water sprays or distractions, not your bare hands.

Now, how can you tell if a capybara is about to bite or is considering biting?

Capybaras don’t just bite out of nowhere.

Like most animals, they give off signals, little warnings that tell you, “Hey, back off.”

Here are the key signs to watch for:

Growling or Clicking Noises

Capybaras aren’t silent creatures.

They’ve got a whole library of sounds, and some of them are red flags.

If a capybara is feeling tense or angry, it might let out a low growl, grunt, or even a sharp bark (yes, like a dog). They also grind or clack their teeth, a classic rodent warning.

One person shared how a capybara started growling and huffing as they got too close.

They took the hint and backed off, which was the smart move.

Here’s the cheat sheet:

- Soft purrs and chirps = chill

- Harsh, loud, or weird noises = not chill

Tense, Fixed Posture (Standing Ground)

A relaxed capybara moves.

An agitated one freezes.

If you approach and it locks eyes, stiffens up, and doesn’t move, that’s a warning.

They might lower their head slightly or puff up their fur just enough to say, “Not comfortable here.”

If it’s not walking away when it normally would?

That’s your sign to give it space.

Keep moving closer, and the next step might be a lunge or a bite.

Retreat Followed by a Turn Back (False Retreat)

Sometimes, a capybara will run off a few feet, then spin around and face you.

That’s not a reset, it’s a bluff.

Basically: “I tried to leave. Now it’s on you.”

If you see a capybara dash and then stop with its snout pointed your way, don’t follow it.

That moment is your window to back off, before it makes its move.

Hair Raised and Scent Marking

Capybaras don’t puff up like cats, but when stressed, their body hair can still lift slightly.

Males, especially, might start scent marking when they feel territorial, rubbing their nose gland (called a morillo) on stuff around them. If you notice white mucus coming from their nose while they’re staring at you, that’s not allergies, that’s a message.

It means: “This is my turf.”

Stick around too long, and the next message might be with their teeth.

Teeth Display or Yawning

Capybaras yawn when they’re sleepy.

But not every yawn is innocent.

If a capybara opens its mouth wide and locks eyes with you, that’s not a nap cue; it’s a threat display. It’s showing you the business end of its incisors.

That’s your preview.

You don’t want the full demo.

Alarm Whistle or Bark (Group Warning)

In groups, capybaras communicate danger with a high-pitched whistle or bark.

If you hear that sound and the whole squad suddenly perks up, you’ve triggered their alert system.

Usually, they’ll scatter and run to water.

But if they feel cornered, they might stay and collectively posture, growling, clacking their teeth, even approaching you in a bluff.

There’s a report of a capybara letting out a sharp bark, and the entire group turned to face the intruder.

If you ever walked into a group acting like that?

Step away.

Calmly.

Quickly.

In Summary

Capybaras bite when they feel like they have to.

Not out of anger. Not for fun.

Triggers include:

- Feeling threatened

- Being cornered or surprised

- Protecting young or territory

- Mistaking food (or your fingers)

- Getting hurt or overwhelmed

They’ll usually warn you first, with a sound, a stance, or a stare.

If you pay attention and respect their boundaries, you can almost always avoid a bite.

I always say:

👉 If the capybara seems even slightly off, step back.

Don’t force the interaction.

Next up, let’s talk about how a capybara’s age and gender can influence how likely it is to bite, because temperament definitely isn’t one-size-fits-all.

Age and Gender Differences in Capybara Aggression

Just like humans and other animals, capybaras have individual personalities – but there are some general trends based on age and sex. Understanding these can help you gauge the bite risk in different situations. For instance, male capybaras tend to be more prone to aggressive behavior (especially when mature), whereas females are usually calmer with humans. Also, a young capybara is far less likely to bite out of aggression than a jaded adult. Let’s break it down:

Bite Risk by Age: Capybaras go through life stages that affect their behavior. Here’s a quick overview in a table:

| Capybara Age | Likelihood of Biting | Behavior Notes |

| Infants (0–3 months) | Very Low – practically nil | Newborn capybaras are extremely docile and reliant on the group. They might give tiny playful nibbles as they begin to explore, but they have small teeth and no aggression. They’re more likely to cuddle than bite. |

| Juveniles (3–12 months) | Low | Young capybaras are curious and social. They may nibble on objects (or your fingers) out of curiosity or during play, but it’s usually gentle. True aggressive biting at this age is rare; they typically run from threats. |

| Adolescents (1–2 years) | Moderate | This is the “teenager” phase. Capybaras reach sexual maturity around 12–18 months, and hormones kick in. Young males, especially, may start testing dominance – some go through a phase around 6–12 months where they get a bit irritable or bold. You might see adolescent males harassing each other or even mouthing at people more. Bites can happen if they aren’t handled carefully, though many capybaras remain sweet. (Not all young males go through a bratty phase, but a few do.) Females at this age might start mothering younger ones, but generally remain gentle unless provoked. Overall bite risk is still not very high, but it’s higher than in infancy. |

| Adults (2–5 years) | Higher | Adult capybaras are in their prime. Males at this stage are often territorial and will assert dominance; this is when serious aggression can appear. A dominant male will not hesitate to chase or bite to defend his turf or harem. If a human does something threatening, an adult male is the most likely to respond with a bite. Females are typically easygoing with people, even in adulthood – they often stay calm unless they feel their babies are in danger. However, any adult capybara has the physical capability to cause serious injury with a bite, so even a female should be treated with respect. This age range is basically the peak in terms of bite risk because they’re strong, confident, and not yet slowed down by age. |

| Seniors (6+ years) | Moderate | By around 6-7 years, capybaras are getting older (their wild lifespan is about 7–10 years, though in captivity they might live slightly longer). Older capybaras often become a bit more sluggish or laid-back. An older male might have lost dominance to a younger one, making him less aggressive. In general, seniors are less likely to initiate aggression – they’ve seen it all and would rather chill. That said, if a senior capybara is in pain (from arthritis, for example) or is startled, it can still bite. And some grumpy old males remain just as territorial as ever. So while the average bite tendency might decrease, it doesn’t disappear. Always consider that an animal might be extra cranky if not feeling well in old age. |

(Note: The age ranges above are approximate. Capybaras mature quickly – many are effectively “adult size” by 1.5 years old – but behavioral maturity can vary.)

As shown, capybara pups and juveniles are very unlikely to bite out of aggression.

They may nibble during play, more like a guinea pig than a wild animal. It’s usually gentle, curious mouthing, not a true bite.

But that changes with age.

Once a male hits around 1.5 to 2 years old, hormones kick in. And with those hormones comes a little more attitude. You’ll want to start reading his mood more carefully, especially if he’s showing signs of dominance.

Female capybaras are a different story. They don’t have that same urge to fight for rank.

Most stay relatively calm around people even as they grow, unless, of course, they feel their babies are in danger.

People who’ve raised capybaras often say the young ones are sweet, tolerant, and cuddly.

It’s the adult males that can get a little more… opinionated. That doesn’t mean aggressive, just that they need clear boundaries and a little more care when handled.

Male vs. Female – Who’s More Likely to Bite?

If we’re speaking in general terms?

👉 Males are more likely to bite.

Especially when it comes to territorial or dominance-based aggression, not accidental bites during feeding.

In wild social groups, males are the ones constantly testing each other. They chase, nip, and challenge for dominance. Females, on the other hand, tend to have a more peaceful, stable social hierarchy.

One scientific study backs this up clearly:

- 34% of male social interactions were aggressive

- Only 8% of female interactions were

That’s not a small gap; that’s a major behavioral difference.

So what does that mean for you?

If you’re around a dominant male, be cautious. He’s the one most likely to test your boundaries, especially if you get too close or interrupt something he doesn’t like.

Even subordinate males might bite if they’re scared or provoked. But the alpha male is usually the boldest and the most likely to confront humans.

Female capybaras, meanwhile, are often the safest to interact with.

That’s why many zoos and wildlife parks use females for public encounters; they’re mellower and more tolerant of people.

That said, never underestimate mother instincts.

A female capybara with babies may go from calm to don’t-touch-my-child in seconds. And yes, she will bite if she feels her pups are in danger.

So if a female has babies nearby?

Give her plenty of space.

She might be gentle, but she’s still got teeth, and she’ll use them if she feels like she has to.

Another factor:

Don’t put two adult male capybaras in the same enclosure with people around.

That’s a recipe for chaos.

Capybara experts strongly advise against it, especially if you’re farming or keeping them as pets.

Why? Because adult males will fight. And if they’re tussling, things can get rough fast.

Biting, charging, head-butting, and if you’re standing nearby?

You could easily get caught in the middle.

Even if they’re not targeting you, two males in a territorial squabble won’t be thinking about your safety.

The better setup?

✅ One male with a group of females (that mirrors their natural social structure)

✅ Or just females together, they usually get along without the drama

It’s the male-on-male rivalry that causes intentional aggression, and that’s when bites can happen.

Do capybaras calm down with age?

Slightly, yes.

Older males tend to be less confrontational than when they were younger. If a capybara is going to show aggressive behavior, you’ll usually notice it by age 2 to 4.

And here’s the good news:

If your pet male capybara is still chill by age 5?

Chances are, he’ll stay that way.

Some people also choose to neuter male capybaras to reduce hormonal aggression.

And it can help; a neutered male often becomes less territorial and less prone to biting.

Of course, neutering a large rodent comes with its own set of considerations, so it’s a personal decision, often based on temperament and long-term care plans.

Female capybaras don’t really have that rut-like aggression cycle.

Spaying is usually about population control, not behavior management.

In summary…

If you’re worried about getting bitten, here’s the short version:

- Males are the ones to be most cautious around

- Especially if they’re dominant or in breeding season

- Females are generally safer; just be extra respectful around mothers.

- Younger capybaras are less aggressive, but still deserve gentle handling.

- Even a baby can surprise you with a sharp nip (those teeth grow early)

Now that we’ve covered who’s most likely to bite and when,

Let’s talk about something a little more intense…

👉 How strong is a capybara’s bite, and how does it compare to animals you already know?

Coming up next.

Capybara Bite Force: How Strong Is It?

When people talk about animal bites, one question always comes up:

👉 “How strong is it?”

Bite force, measured in PSI (pounds per square inch), gives a rough idea of how much pressure an animal can generate with its jaws. And while capybaras aren’t known for attacking, they’ve got some serious jaw strength behind those giant front teeth.

But here’s the catch…

Unlike dogs or crocodiles, the capybara’s bite force hasn’t been formally measured in scientific literature.

So we don’t have an exact PSI number backed by peer-reviewed studies.

Still, that doesn’t mean we’re flying blind.

What We Do Know About Capybara Bite Strength

Capybaras have powerful jaws and huge incisors built for constant chewing.

They tear through thick plants, stems, and twigs daily, no problem.

Their skulls are solid, and their jaw muscles are designed for endurance and pressure, not quick bites like a predator.

So while we don’t have a lab-verified number, experts agree:

Capybaras can bite hard, hard enough to hurt.

One zoo education source described their bite as around 500–600 PSI, on par with a Rottweiler.

That estimate isn’t scientific, so take it with a grain of salt, but it’s helpful for comparison.

For context:

- Rottweilers are often cited at around 300 PSI

- Some strong dog breeds can hit 400+ PSI.

- And humans? Around 160 PSI, on average

So whether capybaras bite at 300, 500, or something in between, one thing is clear:

They’ve got enough force to puncture skin, crush fingers, or cause serious damage.

Animal Bite Force Comparison (For Context)

| Animal | Approximate Bite Force (PSI) |

| Capybara | ~500 PSI (estimated) – Not officially tested, anecdotal range only |

| Guinea Pig | ~55 PSI – Small, but capable of sharp nips |

| Beaver | ~180 PSI – Built for chewing through wood |

| Human (adult) | ~160 PSI – Molar bite average |

| Dog (avg. breed) | ~230–250 PSI – Depends on size and breed |

| Large Dog | ~300+ PSI – Rottweilers, Shepherds, etc. |

| Alligator | 2,000+ PSI – Just for extreme comparison |

Note: PSI = pounds per square inch of pressure. These figures can vary by source and testing method, but they give a general comparison.

So no, a capybara won’t rip your arm off like a crocodile…

But underestimate those chompers, and you might still end up in stitches.

From the above, you can see a capybara’s bite is likely in the same league as a medium-to-large dog in terms of raw power.

It’s definitely stronger than your typical small pet; guinea pigs, rabbits, and even beavers don’t come close in terms of force.

Capybaras may not match the crushing jaws of a big cat or carnivore (and thank goodness they don’t have fangs), but think about it…

These 100-pound rodents chew through thick reeds, bark, and fibrous plants every day.

Their jaws are built for it, and that same power shows up in their bite.

Real Injuries Prove the Point

We’ve already walked through some disturbing cases:

- A capybara cracked a dog’s ribs and caused fatal internal damage

- A woman needed stitches for a deep thigh laceration.

- A capybara bit through a finger hard enough to draw pools of blood

You don’t get those outcomes unless the bite force is serious.

Whether it’s 300 PSI or 600, the power is there.

Capybara vs. Dog: How They Bite Differently

Dogs have canine teeth designed to puncture and grip. Their jaw shape helps them shake and tear during an attack, classic predator style.

Capybaras don’t do that.

Instead, they use incisors that slice. Think of them like chisel blades; they bite down and pull back. That’s how you get long, slicing wounds instead of the usual two-puncture marks you’d expect from a dog.

One child in Japan had a clean gash from her ear down to the back of her head, a classic example of that slicing motion.

So in some ways, a capybara bite can actually be worse than a puncture.

It’s more like a razor cut than a stab, and it can sever tissue cleanly.

The (Slightly) Good News

Capybaras don’t lock their jaws or thrash like a dog.

Most of the time, they’ll bite once or twice, then let go.

They’re not trying to maul or kill; they just want you gone.

So while the bite is painful and can be dangerous, it’s usually not a continuous attack.

That doesn’t make it safe…

But it’s a little less terrifying than a full-on dog mauling.

Could a Capybara Bite Your Finger Off?

Short answer? Yes, it’s possible.

There’s no confirmed report of a full amputation, but given what we know:

- Capybara teeth are self-sharpening and rodent-strong

- They regularly chew through stems thicker than a human finger.

- And smaller rodents like rats have already proven they can crush bones.

So if a capybara got a clean grip?

👉 It could likely fracture or partially sever a finger.

In Summary

Capybaras have a powerful herbivore bite, not designed for hunting, but still more than capable of serious damage.

It’s not crocodile-level power, but it’s comparable to a large dog bite in severity.

And that means:

- You should treat capybara bites as medical emergencies

- Their mouths may also carry unique bacteria that need proper cleaning.

- Even one bite can lead to stitches, infection, or long-term scarring.

Respect their bite like you’d respect a Rottweiler’s.

Coming up next:

Let’s look at whether capybaras as a whole should be considered “dangerous animals”, and what you can do to keep your interactions safe.

Are Capybaras Dangerous to Humans?

Capybaras have become internet icons for being the “friendliest animal alive.”

You’ve probably seen the memes, capybaras chilling with ducks, dogs, cats, monkeys, you name it.

And the truth is… they are remarkably docile.

But are they dangerous to humans?

Mostly no.

With a few important caveats.

Capybaras aren’t aggressive by nature.

They’re herbivores, they don’t see humans as food, and they’re not known for territorial aggression toward people, unlike, say, wild boars or hippos.

In South America, people swim alongside wild capybaras all the time without issues.

Zoos often run capybara encounter programs where guests can pet or feed them under supervision.

And if you talk to capybara owners?

Most will tell you their pet is a big sweetheart that would rather snuggle or walk away than lash out.

But here’s the thing:

“Not dangerous” doesn’t mean “totally safe.”

Capybaras are still wild animals.

They have instincts. And those teeth are no joke.

If you grab one the wrong way, get too close to a protective mother, or crowd them when they feel trapped, they absolutely can bite.

Think of it like this:

🦌 A deer isn’t dangerous most of the time.

But if you corner it? You could get kicked in the ribs.

Same with a capybara.

They won’t chase you down… but if you give them a reason, they can hurt you.

So… Can Capybaras Cause Serious Injury?

Yes, on an individual incident level, capybara bites can absolutely be dangerous.

We’ve seen:

- A dog was killed by bite wounds

- A woman hospitalized with deep thigh lacerations

- A child with a head wound that required nine stitches

These are not trivial injuries.

You don’t want to be on the receiving end of that kind of bite.

But Are Capybara Attacks Common?

Not at all.

Capybara attacks on humans are extremely rare.

Far rarer than dog attacks, for example.

Statistically, they’re one of the least dangerous large wild animals you’ll ever meet.

They’re more like cows or horses, generally gentle, but capable of hurting you if mishandled.

One wildlife expert in Colombia said it well after reviewing a lake attack video:

“Don’t be fooled by the cute videos. They’re still wild animals.”

And that’s really the mindset to have.

Are Capybara Bites Fatal?

So far? No human deaths have been reported from a capybara bite.

Even in the worst cases, like the woman bitten multiple times while swimming, victims survived.

Capybaras aren’t predators.

They don’t have a kill instinct toward humans.

But their bites can still be dangerous due to:

- Trauma (heavy bleeding, nerve damage)

- Infection (rodent mouths carry unique bacteria)

Treat capybara bites seriously, and with quick medical attention, recovery is highly likely.

A Quick Reality Check

There’s a claim floating around:

“A capybara can’t do a lot of damage to an adult human.”

Honestly? That’s misleading.

While it’s true they’re not trying to wound you mortally, the injuries they cause are nothing to shrug off.

A full-grown human may survive a bite, but deep cuts, blood loss, or infection are still real risks.

And kids?

Far more vulnerable, especially if a bite lands near the neck, head, or arteries.

That nine-stitch head wound on a child in Japan?

Just a few inches in the wrong direction and it could’ve been catastrophic.

Final Take

Capybaras are not aggressive animals.

They don’t stalk people. They don’t hunt.

A healthy, unprovoked capybara in the wild will almost always flee into water rather than confront you.

The danger comes from one thing: human error.

Grab them. Corner them. Crowd their pups.

That’s when accidents happen.

In captivity, they’re often very safe, especially if raised well and socialized.

I’ve personally pet a capybara that acted calmer than most golden retrievers.

It munched lettuce while I scratched its back. Total chill.

But the staff gave one reminder:

❗ Don’t touch its face.

❗ Don’t stick your fingers near its mouth.

Common sense stuff, and it made all the difference.

Safety Tips to Avoid Capybara Bites

The best way to deal with a capybara bite? Don’t give it a reason to happen in the first place.

Capybaras aren’t naturally aggressive. They don’t go looking for a fight. Most of the time, they just want to graze, soak, and chill in peace. So if you’re mindful of their comfort and body language, bite risk stays low.

Here are a few smart, friendly tips to keep things safe, whether you’re meeting one at a zoo, on a trail, or in your own backyard.

Give Them Space

Capybaras may look cuddly, but they’re still wild animals. If you see one lounging by a river or nibbling in a park, enjoy it from a few meters away. Don’t run up to a phone for a selfie or try to touch it when it’s not inviting contact.They may lash out if they feel boxed int, not because they’re mean, but because they don’t see another option. At zoos or farms, follow the staff’s advice on how close to get and what kind of touch is okay. As a general rule, if the capybara comes to you, great. If it doesn’t, let it be.

Avoid Hand-Feeding

This one catches people off guard. Capybaras can’t see directly in front of their nose; they rely on scent and feel. So if you’re holding a carrot and your finger smells like a carrot? You might get nipped. Always place food on the ground or in a tray. If you’re hand-feeding with supervision, keep your palm flat and fingers together, like you would with a horse. Never dangle food above their head or make them jump for it. That kind of excitement can turn a friendly snack into an accidental bite.

Supervise Children Closely

Capybaras and kids might look like a sweet match, but don’t let the cuteness fool you. Children should never be left alone with capybaras, even in petting areas. No chasing, grabbing, or loud shouting. Kids need to be calm, slow, and gentle, and always within arm’s reach of an adult. Remember: a child’s face is right at bite level. In the Japan incident, it’s likely the kids got too close too fast. If capybaras are part of your family day out, teach your kids how to interact safely before they get too excited.

Approach Calmly (If at All)

If you’re allowed to touch a capybara, whether it’s your pet or part of a zoo encounter, don’t walk in like a threat. Crouch slightly, move slowly, and approach from the side so they can see you. I usually extend a hand and let them sniff me first. If they walk away or turn their back, take the hint and don’t push. Looming over them makes you look like a predator, and nobody relaxes when they’re being towered over.

Learn Their Body Language

Capybaras will tell you when they’ve had enough, but only if you’re paying attention. Growling, barking, freezing in place, puffed-up fur, bared teeth… these are all signs to back off. If you ignore those warnings, a bite is next. Stay calm, don’t run, and give them space. Nine times out of ten, they’ll settle back down once they realize you’re not a threat.

Don’t Pick Up or Restrain an Adult Capybara

They might be cuddly-looking, but capybaras are heavy and strong, and most do not like being lifted or restrained. If you try, they’ll struggle, and that’s how scratches and bites happen. Unless you’re a trained professional (or dealing with a medical emergency), never try to carry one. Guide with food, not force. If you must pick up a juvenile, support the entire body and keep it brief. And remember: bad handling once can lead to long-term fear of being touched.

Be Careful During Mating Season

Testosterone changes things. During mating season, especially if you’re around wild groups or have an intact male at home, be extra cautious. Males may become pushier, more territorial, or just quicker to react. You might even smell unfamiliar to them and trigger a defensive response. In some regions, breeding happens year-round, so if you’re not sure, treat every adult male like he might be on high alert. Give them space and don’t test their patience.

Never Get Between a Capybara and Water

If you’re near water and see capybaras heading toward it, step aside. Water is their safe zone. If you accidentally block the path, you force them to choose between freezing… or charging through you. And trust me, a stampede of 100-pound rodents won’t pause to politely go around. They’ll run straight over anything in the way. Always be mindful of exits and escape routes when you’re near capybaras.

Mind Other Animals

Capybaras might be okay with birds or other capys… but dogs? Different story. Capybaras can mistake dogs for predators, especially if they bark, lunge, or get too curious. If you’re walking your pup in an area where capybaras live, keep them leashed and well away. Many bite cases start because a dog got too close. The same goes for bringing treats or food near capybaras when you’ve got other animals with you; it can trigger tension fast.

Pet Capybara Precautions

Thinking of owning a capybara? Socialization is key. Start young. Handle them gently, without force. Don’t roughhouse like they’re a puppy; they’re not built for it. Use calm repetition, treats for good behavior, and patience. Trim nails regularly (carefully), and ask a vet if their incisors ever need dulling (only if absolutely necessary and done professionally). Most important: never house two males together, and if you don’t plan to breed, talk to an exotic vet about neutering. Give them space, water access, and a peaceful environment.

A well-adjusted capybara is calm, curious, and safe to be around.

A stressed one? That’s where trouble starts.

In Summary

Capybaras are not out to hurt people.

They’re generally safe, low-risk animals, far from being “dangerous” in the way predators or venomous creatures are.

But they’re still animals with instincts, strength, and teeth.

Treat them with respect, and you’ll stay safe.

Push their limits, and you might get bitten.

Up next: Let’s go over practical safety tips so you can enjoy time with capybaras without ending up in the ER.